Improving Competitive Skills

Introduction

Back in 2014, I started Competitive Programming, and I reached Codeforces Grandmaster after about 6 years. In 2022, I started Chunithm and reached 16.00 after ~3 years (1300-ish play counts). I never had a target for these two games (well, I did, but only when I was already near the milestones), and only competing/playing as my hobbies. Those ranks are admittedly still very far from the pinnacle of each field, but I do take pride on achieving them. Contrary to what people may think about me, I am not really a competitive person, nor am I an achiever.

The time I took to achieve those was definitely not the quickest one, and I was never under the improvement mindset while engaging in those activities. However, I do notice some common patterns/frameworks that can probably be applied to other competitive fields if you really aim for improvement.

The general advice to improve is always this one word: “practice”. No matter what kind of guidance, coaching, or tips you receive, you will never improve if you do not have the patience to practice. But here, I will try to point out a few things that might help with improvement from the point of view of a Competitive Programmer and Chunithm Player (both can be coincidentally abbreviated as CP-er).

Since I am explaining things for both fields as once, I may use these two words interchangeably:

- solving and playing;

- problem and chart;

- rating and level.

Note that the source of everything laid down here is “trust me bro”.

Skill Floor vs Ceiling

Some of the knowledge from this section is actually borrowed from this document: Mentality for Improvement in Rhythm Games. I do believe some of them can be applied to other competitive fields as well.

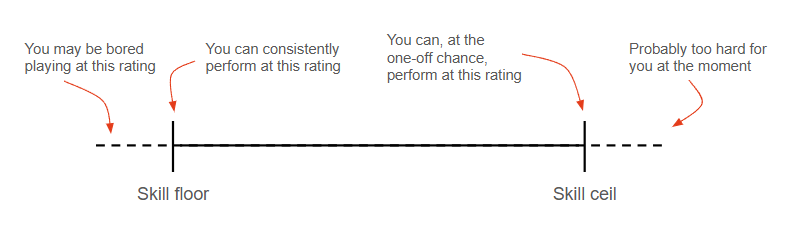

First is to define:

- Skill floor: the (maximum) level at which you are able to perform consistently.

- Skill ceiling: the level at which you can sometimes perform beyond your current ability.

To illustrate:

With that said, I do believe your current skill level can’t actually be defined as a single number, but more accurately with a range. Your current rating must be somewhere in that range.

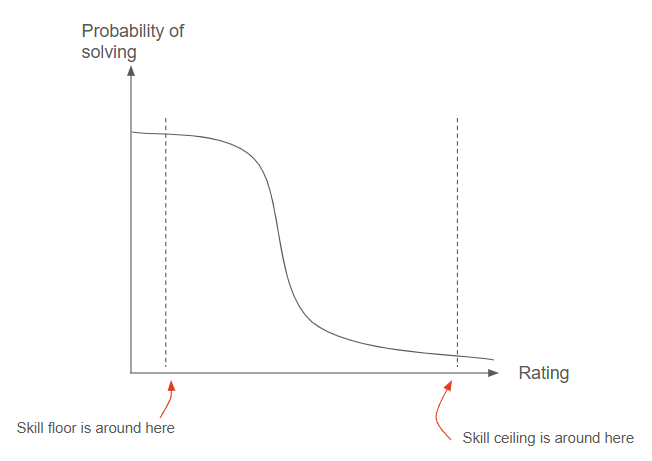

I believe it can be further generalised as the sigmoid function:

But you can just stick to the single line thing for simplicity.

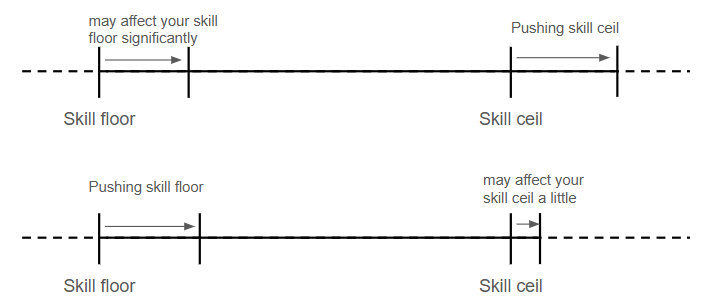

Pushing your floor and ceiling may require a different kind of practice.

Skill Floor

What you need to improve your skill floor in terms of:

- Chunithm: you need to be exposed to a lot of charts (and hence patterns) and be able to consistently perform at SS+ or SSS performance (or whatever standard that is high enough for you).

- Competitive Programming: you need to be exposed to a lot of problems (and hence topics) and be able to consistently solve them within a certain time range.

So to push your skill floor, it naturally follows that for:

- Chunithm: play charts at a level lower than your rating (e.g. your rating - 3) and try to achieve a high performance across different charts consistently.

- Competitive programming: solve problems below your current rating (e.g. your rating - 200) and try to solve them within, say, 20 minutes. Do this routinely, possibly as a warm-up.

Skill Ceiling

You only need to be able to perform beyond your skill level for specific problems or charts.

To push your skill ceiling on:

- Chunithm: pick a chart, aim to SSS (or whatever performance that is atypical for you at that moment) it by playing repeatedly (possibly across sessions). You may also want to study the chart offline.

- Competitive Programming: pick a problem of your choice, may be from your favourite topic or a topic you want to master, solve it at your leisure (e.g. during commute, inside a plane). The aim is to rewire your brain so that it can solve problems of a higher rating (or problems you were unfamiliar with); hence, you will require less effort to solve problems of the same rating in the future.

Which skill to push?

Both skill floor and ceiling are not independent. Pushing one may affect the other, but I do believe pushing skill ceiling is more effective for overall improvement.

To illustrate:

Depending on your goals, the skill you should focus on may differ.

| Goal | Focus | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Chunithm rating | Skill ceiling | The rating is calculated only by your top plays |

| Onsite or annual contests (IOI/ICPC/Hacker Cup) | Skill floor | You only had one chance to perform well, skill floor is important if you want a medal |

| Online weekly contests | Balanced | Skill floor to not lose too much rating, skill ceiling for rating boost. Your rating fluctuates if the gap between them is huge. |

But that does not mean you should solely focus on one skill.

For IOI training, for instance, I think focusing on the skill floor is more important only during the last 3 months before the contest (they may also act as a mental boost). Before that, improve your ceiling as much as possible. As another food for thought, I wonder if having “rank variations” is a good metric when selecting the country’s delegation, since consistency is also a key factor to win a medal.

For online programming contests, you might need to hope that the contest suits well with your skillset, and possibly avoid contests where the authors are infamous for topics you dislike. That being said, you do not really need to master all topics (i.e. a solid skill floor), and generally skill ceiling is more important if you aim to raise your max rating.

Recommendation Problems/Charts

How do you pick charts to play or problems to solve? Just pick anything at random (within your skill range, of course). Or better, pick anything that you find interesting, since it is essentially random too! You can also use any randomiser tools you find to pick things for you.

A few of these methods, however, do NOT really help in boosting your progress (at least for me).

- chunirec BEST entries stats.

- Problems that were also solved by your peers.

- Rating up folder on Chunithm

- Problems sorted by most solvers

They are all essentially random, so do not feel demotivated if they did not boost as you might have expected, even though some of those lists came from statistical data. You can, of course, use them as your “randomiser”, but do not expect any rating boost from those lists.

If you have a good trainer that understand your current skillset, then this trainer may actually help you in improving your performance by giving you pointers or actually recommending problemset that matches your skill.

Coaching

This section is a bit loosely written, so you may skip it. I do not have much teaching experience, and I do not like to teach (it’s fun once in a while, but not as a job). I’m also not a very good teacher as I often struggle to pour my thoughts into words. Yes, this entire blog is a giant irony.

Does a trainer or a coach actually help? They sure do, but only up to a certain level. They act as a catalyst, so you will still need to practice and act on your own. Meaning that, do not solely depend on their guidance or wait for their instructions.

A coach may help you to kickstart, so you do not have to reinvent the wheel for every basic stuff. They may help pointing out the topic/pattern you are weak at. They may be able to see that you have solidify your fundamentals and ready to move to the next level.

However, coaches also have their limit. At some point, you may already be performing beyond what the coach can see. Then, the coach can only give you a random problemset for the sake of “training”. Can you still see them as a coach at that point? At least he is your new randomiser (lol).

Coaching and playing are two different skills. A good coach may not perform well in a competition (they are only good at identifying things to learn). Similarly, a good player may not be able to teach well (they only know what is best for themself, not guiding others). Surely, there are correlations between the two, but identifying a good coach is certainly not easy as it is hard to get a good metric for it.

Can a good coach be identified by the number of successful students they have? Not necessarily. Take the Indonesian CP lesson market as an example (which is a hot market at the time of this writing). Even if a certain camp advertised that they dominated the medal ranking, but when you see the bigger picture, they simply have an enormous number of students, and some of them happen to win by chance. That is, statistically, you gained no edge to win a medal by joining that camp.

What I am trying to say in this section is that, do not waste your time finding a good coach; any decent coach with decent experience will do (if you need one). Even if you find a good one, you’ll need to be independent at some point, especially if you aim to win something.

Milestones

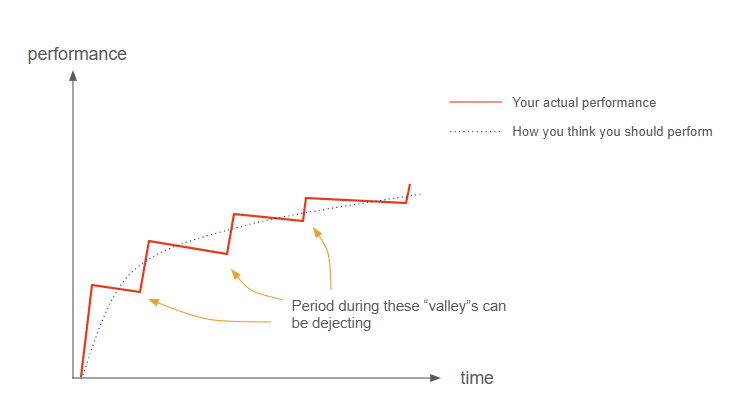

Progress is not linear. I think it is more of something like this.

So do not be demotivated when you can’t seem to improve even when you were very near to your next milestone. It might be that you have unfortunately hit your next wall that is very near to your milestone.

When you’re practising, you are actually accumulating your latent skill that is yet to be realised into your actual skill. Your body needs some time to convert this latent skill into an acquired skill.

I also believe that the accumulated latent skill can only hold a finite capacity. So it is important to take a break and let your body catch up with what you have trained with. This also implies that training one day before competition day isn’t particularly useful.

Practice

All in all, what you need to do is consistently practice. The insights above may help, but I believe they won’t give you that large of an advantage even if you know them beforehand. By practising, you may also discover your own style.

I also believe that a lot of competitive skills are ultimately pattern recognition (so if you have a good memory, you are better at improving competitive skills). In competitive programming, once you are familiar with how problems are commonly set up, your brain will automatically tell you how to approach those problems. Similarly, in Chunithm, your hand muscles just automatically move when you see certain patterns. That pattern recognition can only be developed through a lot of practice.

Closing

This article may possibly be yet another “how to improve” article, but I often like to explain things from my perspective.

A few other things I did (or did not do) but I couldn’t generalise them into a single framework that fit within the article, possibly because they are indeed irrelevant:

- I sometimes watch people play Chunithm on YouTube, and possibly shadow the play (so I’ll need to make sure the chart is indeed within my skill level).

- Studying to execute a pattern using slow motion, or figuring out which finger to play which notes, are not helpful. You can execute the pattern naturally when the time comes.

- I do not watch people livestream problem solving, and I do not find listening to their train of thought to be useful. People imagine things differently and can have very different thought processes.

- I think I give up pretty easily. I usually do not think of a problem for days, and usually just look at the editorial after 20-30 minutes of thinking, sometimes even under 5 minutes.

- I like to think of a problem to procrastinate during my actual work. I think a lot while commuting during my active CP years too.

A few things that I would tell my past:

- Study 4k patterns using fingers earlier. Execute stairs and rolls using your index and ring fingers.

- Competitive programming costs you a LOT of time. It costs that much that it literally has to be part of your life (imagine requiring 1 hour per problem, or 5 hours per contest for a single feedback on your performance). Be sure that you are not leaving things you like behind, and the time that you dedicate is indeed worth it.

Now, as per tradition, I will also show my best charts the moment I reached R16 Chunithm: